Punctal Plugs: An Essential Tool in the Management of Dry Eye

Alan G. Kabat, OD, FAAO

This educational article is also available as a downloadable PDF.

According to current studies, as many as 30 million American adults may have symptomatic dry eye disease (DED).1,2 Many of these individuals elect to self-manage their symptoms, usually turning to over-the-counter eye drops. A smaller percentage seek the advice of eye care professionals, who may recommend a myriad of treatment options such as artificial tears, gels or ointments, lid hygiene products, topical or oral pharmaceuticals and nutritional supplements. Less commonly, physicians may employ in-office procedures designed to mitigate symptoms and promote ocular surface health. And although a range of new technologies has been introduced in recent years, no single treatment has emerged that can successfully address all cases of DED.

According to current studies, as many as 30 million American adults may have symptomatic dry eye disease (DED).1,2 Many of these individuals elect to self-manage their symptoms, usually turning to over-the-counter eye drops. A smaller percentage seek the advice of eye care professionals, who may recommend a myriad of treatment options such as artificial tears, gels or ointments, lid hygiene products, topical or oral pharmaceuticals and nutritional supplements. Less commonly, physicians may employ in-office procedures designed to mitigate symptoms and promote ocular surface health. And although a range of new technologies has been introduced in recent years, no single treatment has emerged that can successfully address all cases of DED.

Historical overview

Punctal occlusion has been a recognized therapy for managing disorders of the ocular surface since the 1930s.3,4 While the earliest procedures involved surgical cautery, the use of implantable devices to obstruct tear drainage was realized in the 1960s, with the contemporary punctal plug being developed by Freeman in the mid-1970s.5,6 The concept of punctal occlusion involves a very simple and straightforward mechanism of action. By creating a physical obstruction to tear drainage through the canaliculus, clinicians can provide both increased tear volume and enhanced tear residence time on the ocular surface.7 In essence, a punctal plug does for the eye what a drain stopper does for a bathtub: it allows the reservoir to fill more completely, and retains that moisture for a longer period of time. Studies have shown that this simple procedure helps to improve functional visual acuity as well as Schirmer scores, tear break-up time and goblet cell density.6,7 Additionally, punctal occlusion reduces vital dye staining of the ocular surface, and alleviates many symptoms associated with DED.8,9

Through the 1990’s and early 2000’s, punctal plugs were a mainstay of dry eye therapy. As recently as 2003, experts were recommending punctal occlusion for even mild DED (defined as symptoms of dryness without observable signs), typically incorporating this treatment as second-line therapy for those who failed to attain symptomatic relief with tear substitutes alone.10,11 However, this strategy changed after the FDA approval of cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion for DED. The novelty of this new pharmaceutical agent, combined with the reimagining of DED as an inherently inflammatory condition, lead to a radical shift in conventional thinking. Both the Delphi Panel (2006) and the International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS, 2007) developed treatment algorithms that recommended topical anti-inflammatory therapies and even some oral therapies prior to considering punctal plugs.12,13 Simultaneously, eye care providers saw third party reimbursement for punctal occlusion fall significantly. From 2001 to 2008, the maximum allowable fee for this procedure under Medicare declined by more than 50%, causing many to essentially abandon this form of therapy.

As we know however, attitudes are fluid. Therapies that have been regarded as “old school” or “last resort” occasionally find their way back to the forefront of patient care. To this point, the most current and comprehensive publication on DED—the TFOS DEWS II Report (2017)—actually recommends earlier intervention with punctal plugs.14 In the new treatment algorithm for staged management of DED, experts list punctal occlusion just after the use of non-preserved ocular lubricants, but before prescription drugs such as topical anti-inflammatories.14 The reason for this turnaround may be a series of recent studies demonstrating the benefits of treatment with punctal plugs.

- Roberts and associates (2007) compared treatment with a) punctal plugs, b) topical cyclosporine emulsion, and c) a combination of both in patients with moderate DED. After 6 months, researchers noted statistically significant improvement for both tear volume (Schirmer score) and decreased frequency of artificial tear use in all groups, but found the greatest change from baseline in patients using both therapies simultaneously.15 They concluded that “There may be an additive effect of topical cyclosporine and punctal occlusion that would merit their concomitant use.”15

- Qiu and associates (2012) compared treatment with artificial tears vs. punctal plugs in patients with DED. Their results showed equivalent benefit in terms of diminished corneal staining, improved contrast sensitivity and relief of dry eye symptoms. Patients in the punctal plug group however showed greater improvement in terms of tear stability (fluorescein tear break-up time) and tear volume (Schirmer score).16

- Tong and associates (2016) evaluated tear cytokine levels as well as clinical signs and symptoms before and after punctal plug insertion in patients with moderate DED. After three weeks, there was no significant increase in overall cytokine or matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) levels, but global symptom scores diminished while tear break-up time, Schirmer test scores and corneal staining all showed statistically significant improvement.17

- In a follow-up publication, Tong and associates (2017) analyzed the effect of punctal occlusion on wider array tear proteins. Interestingly, they found that a subset of patients with lower Schirmer scores at baseline showed a decrease in inflammatory tear proteins along with an increase in lacrimal proteins that support ocular surface health.18 These results support the early use of punctal plugs in management of DED patients with diminished tear volume.

When and where to plug

While we know that punctal plugs are not ideal for every DED patient, it is important to understand where they may play an appropriate and essential role in therapy. First and foremost, punctal plugs should be considered in all cases of aqueous-deficient DED, i.e. those individuals who show diminished tear volume (as measured by Schirmer strips, phenol red thread test or direct measurement of the tear meniscus), reduced tear stability (rapid tear break-up time) and a symptom profile consistent with dry eye. This includes patients with underlying systemic conditions that predispose toward DED, such as Sjögren syndrome or rheumatoid arthritis, as well as those taking medications that are known to reduce tear production. Second, patients who develop DED as a consequence of contact lens wear or refractive surgery may also be excellent candidates for punctal plugs. Recent studies corroborate this recommendation.19,20 Third, punctal plugs may benefit patients who are consistently using topical anti-inflammatory medications for DED (e.g. cyclosporine or lifitegrast) but who nonetheless continue to be symptomatic. Additionally, those patients with incomplete lid closure or corneal irregularities that affect tear stability should be considered for punctal plugs. It is important to understand also that punctal occlusion does not preclude the concurrent use of artificial tears. On the contrary, artificial tears may provide an additional mechanism for relief of sporadic symptoms, but studies have shown that punctal plugs help to significantly reduce the need for frequent drop instillation in patients with DED.15,20,21

Billing, coding & reimbursement

Punctal occlusion is unique among early staged DED therapies in that it is directly reimbursable by most third-party insurers. Neither artificial tears nor topical pharmaceuticals affords the practitioner any potential revenue stream aside from the office visit, and other in-office procedures such as lid margin debridement or Meibomian gland expression represent non-billable services. For a practice that relies heavily on medical insurance, the most profitable approach to DED management always incorporates the use of punctal plugs.

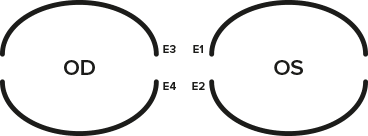

In order to properly submit a claim for punctal occlusion, the billing party must use CPT code 68761. If more than one punctum is occluded on the same day, modifiers should be used. The right and left eye may be designated as -RT and -LT, or punctum-specific codes may be used (see image). The -50 modifier may also be used, indicating that the procedure was performed bilaterally. Unfortunately, not all payers recognize the same modifiers. It is important to note that the multiple surgery rules apply to punctal occlusion; when more than one punctal plug is inserted during the same office visit, the first procedure is reimbursed at 100% while each additional procedure is reimbursed at 50% of the allowed fee. Another important point to remember when billing minor surgical codes such as 68761 is that the reimbursement includes the office visit. For this reason, the practitioner should not bill simultaneously for the encounter using a 920XX or 992XX code. The post-operative period for punctal occlusion is 10 days, so an office visit submitted during this time (for the same condition) will not be considered. It is also important to use a proper ICD-10 code when billing for punctal occlusion. Some of the diagnoses that support 68761 include dry eye syndrome (H04.12X), keratoconjunctivitis sicca (H16.22X), unspecified superficial keratitis (H16.10X), filamentary keratitis (H16.12X), exposure keratitis (H16.21X), and sicca syndrome with keratoconjunctivitis (M35.01).

In order to properly submit a claim for punctal occlusion, the billing party must use CPT code 68761. If more than one punctum is occluded on the same day, modifiers should be used. The right and left eye may be designated as -RT and -LT, or punctum-specific codes may be used (see image). The -50 modifier may also be used, indicating that the procedure was performed bilaterally. Unfortunately, not all payers recognize the same modifiers. It is important to note that the multiple surgery rules apply to punctal occlusion; when more than one punctal plug is inserted during the same office visit, the first procedure is reimbursed at 100% while each additional procedure is reimbursed at 50% of the allowed fee. Another important point to remember when billing minor surgical codes such as 68761 is that the reimbursement includes the office visit. For this reason, the practitioner should not bill simultaneously for the encounter using a 920XX or 992XX code. The post-operative period for punctal occlusion is 10 days, so an office visit submitted during this time (for the same condition) will not be considered. It is also important to use a proper ICD-10 code when billing for punctal occlusion. Some of the diagnoses that support 68761 include dry eye syndrome (H04.12X), keratoconjunctivitis sicca (H16.22X), unspecified superficial keratitis (H16.10X), filamentary keratitis (H16.12X), exposure keratitis (H16.21X), and sicca syndrome with keratoconjunctivitis (M35.01).

Product considerations

A wide variety of punctal plugs are currently available from numerous manufacturers, but in general there are three basic categories: short-term temporary plugs, long-term temporary plugs, and permanent plugs. The short-term variety, such as the VeraC7,™ are composed of collagen and designed to be absorbed completely in 7-10 days. Practitioners should think of collagen plugs as a diagnostic tool to determine if punctal occlusion will be well-tolerated by the patient. Long-term temporary plugs are composed of synthetic polymers that absorb more slowly than collagen. The Vera90™ is made of ε-caprolactone/L-lactide copolymer (PCL), a substance that absorbs in 60 to 180 days. Lacrivera’s temporary plugs are 2.0 mm in length and reside completely within the canaliculus once inserted. They come in 0.3, 0.4 and 0.5 mm diameters to accommodate a range of punctal openings. Long-term temporary plugs are an excellent option for patients that may be expected to have self-limited DED issues, such as those anticipating refractive or cataract surgery. In addition, these can be used for patients who have been identified as good candidates for punctal occlusion, but suffer from awareness with conventional punctal plugs that have exposed caps along the lid margin.

Permanent plugs are composed of non-dissolvable materials, most commonly silicone, although some hydrogel and acrylic devices are also available. The VeraPlug™ and VeraPlug™ FlexFit™ are both silicone plugs designed in the Freeman style. Both products are available in multiple sizes to accommodate various sized punctal openings, but the newer FlexFit™ offers a unique nose technology that collapses upon insertion, thereby allowing for easier sizing and placement. Lacrivera also offers a product designed to provide partial occlusion. The VeraPlug™ Flow has a narrow inner channel that reduces, but does not completely eliminate tear outflow. It is ideally suited for patients who benefit from punctal occlusion, but experience epiphora with standard permanent plugs.

Regardless of which occlusion device is used, billing and coding remains consistent. Reimbursement is identical for short-term collagen, long-term synthetic inserts and silicone punctal plugs, although most third-party payers limit the frequency that a provider can bill for this service. Checking with the patient’s carrier before carrying out these procedures helps to avoid denials and appeals.

The take-home message

While punctal occlusion may not be a new therapy, it has proven its value time and time again. Despite setbacks, research and expert consensus validates this treatment modality as a beneficial aspect of DED therapy. Earlier intervention with punctal occlusion makes sense in a great many cases, particularly those outlined here. And while addressing ocular surface inflammation is of great importance, concomitant tear conservation with punctal occlusion appears to further diminish signs and symptoms in those with DED. Unquestionably, these devices should be utilized much more frequently than current trends indicate. Incorporating the use of punctal plugs in one’s practice helps to expand its therapeutic reach, enhance its financial health and achieve greater overall patient satisfaction.

REFERENCES

1. Paulsen AJ, Cruickshanks KJ, Fischer ME, et al. Dry eye in the beaver dam offspring study: prevalence, risk factors, and health-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(4):799-806.

2. US Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population for selected age groups by sex for the United States, States, Counties, and Puerto Rico Commonwealth and Municipios: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014. http://files.hawaii.gov/dbedt/census/popestimate/2014-state-characteristics/

3. Beetham WP. Filamentary Keratitis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1935;33:413-35.

4. Macmillan JA, Cone W. THE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF KERATITIS NEUROPARALYTICA BY CLOSURE OF THE LACHRYMAL CANALICULI. Can Med Assoc J. 1937 Oct;37(4):348-50.

5. Freeman JM. The punctum plug: evaluation of a new treatment for the dry eye. Trans Sect Ophthalmol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1975 Nov-Dec;79(6):OP874-9.

6. Adams AD. Silicone plug for punctal occlusion. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1978;98(4):499.

7. Chen F, Shen M, Chen W, et al. Tear meniscus volume in dry eye after punctal occlusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010 Apr;51(4):1965-9.

8. Goto E, Yagi Y, Kaido M, et al. Improved functional visual acuity after punctal occlusion in dry eye patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003 May;135(5):704-5.

9. Dursun D, Ertan A, Bilezikçi B, et al. Ocular surface changes in keratoconjunctivitis sicca with silicone punctum plug occlusion. Curr Eye Res. 2003 May;26(5):263-9.

10. Murube J. Surgical treatment of dry eye. Orbit. 2003 Sep;22(3):203-32.

11. Calonge M. The treatment of dry eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001 Mar;45 Suppl 2:S227-39.

12. Behrens A, Doyle JJ, Stern L, et al. Dysfunctional tear syndrome: a Delphi approach to treatment recommendations. Cornea. 2006 Sep;25(8):900-7.

13. Management and therapy of dry eye disease: report of the Management and Therapy Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007 Apr;5(2):163-78.

14. Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, et al. TFOS DEWS II Management and Therapy Report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):575-628.

15. Roberts CW, Carniglia PE, Brazzo BG. Comparison of topical cyclosporine, punctal occlusion, and a combination for the treatment of dry eye. Cornea. 2007 Aug;26(7):805-9.

16. Qiu W, Liu Z, Zhang Z, et al. Punctal plugs versus artificial tears for treating dry eye: a comparative observation of their effects on contrast sensitivity. J Ocul Biol Dis Infor. 2012 Nov 29;5(1):19-24.

17. Tong L, Beuerman R, Simonyi S, et al. Effects of Punctal Occlusion on Clinical Signs and Symptoms and on Tear Cytokine Levels in Patients with Dry Eye. Ocul Surf. 2016 Apr;14(2):233-41.

18. Tong L, Zhou L, Beuerman R, et al. Effects of punctal occlusion on global tear proteins in patients with dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2017 Apr 19. pii: S1542-0124(16)30285-3. [Epub ahead of print]

19. Li M, Wang J, Shen M, et al. Effect of punctal occlusion on tear menisci in symptomatic contact lens wearers. Cornea. 2012 Sep;31(9):1014-22.

20. Alfawaz AM, Algehedan S, Jastaneiah SS, et al. Efficacy of punctal occlusion in management of dry eyes after laser in situ keratomileusis for myopia. Curr Eye Res. 2014 Mar;39(3):257-62.

21. Nava-Castaneda A, Tovilla-Canales JL, Rodriguez L, et al. Effects of lacrimal occlusion with collagen and silicone plugs on patients with conjunctivitis associated with dry eye. Cornea. 2003 Jan;22(1):10-4.